30/06/2017

Print PageTargeted countermeasure for altering tumors

In Germany 5.530 women and 9.500 men were diagnosed with renal cancer in 2012. Renal cancer is particularly aggressive due to the frequent occurrence of metastases: the kidney belongs to the most blood-supplied organs, which causes proliferating cancer cells to increasingly spread through the blood- and lymphatic vessels.

“Nowadays, metastasized renal cancer is longer controllable in many patients than in the past” explains Holger Sültmann. Sültmann researches the genetic alteration in cancer cells together with his colleagues in the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) at the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT), the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the Department of Urology at the Heidelberg University Hospital. “Even if resistances occur – which unfortunately is the case with most patients after a certain time – targeted therapeutics can effectively counteract, if the adequate medication is known.”

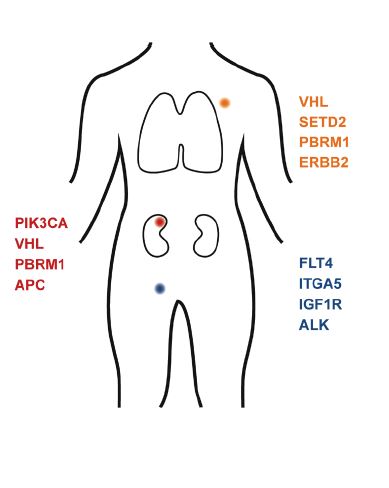

In the clinical trial MORE (Molecular Renal Cancer Evolution), Sültmann, Carsten Grüllich of the NCT and colleagues from the University Hospital Heidelberg examine which medication could be effective, if the cancer cannot be controlled after a tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. In the study, initiated in 2014, the scientists of Heidelberg analyze the molecular alteration in metastasized clear cell carcinoma and the development of resistances occurring in this targeted therapy. “For the first time, we have analyzed the full genetic profile of metastases in patients with advanced renal carcinoma, who have priorly been treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and were no longer responsive to the treatment”, as physician and scientist Grüllich reports.

tyrosine kinase inhibitors purposefully intervene into the metabolism of the tumor cell and thereby halt its growth and the spread of metastases.

The first results released from the MORE-Study now show that metastases which occur in patients despite treatment cause additional mutations in known cancer genes, as opposed to the original tumor. The BRCA1 or “Breast cancer gene” is one of them among others, which is also involved in the development of ovarian – and prostate cancer. “In some of these cancers, the drug Olaparib has been successfully implemented to prevent cancer cells from DNA repair, causing a programmed cell death” says Stefan Duensing from the Department of Urology at the Heidelberg University Hospital. According to Duensing this approach could also be considered for patients with renal cancer and mutations of the BRCA1 gene.

However, Sültmann acknowledges that the inclusion of the mutation patterns of metastases in the treatment plan of renal cancer would require a confirmation of the results in the form of a larger patient population. Grüllich adds that “next to molecularly targeted therapies we also have to consider other treatment options, such as immunotherapy for example.”

Sültmann sees decisive advantages for patients and the health care in the molecular approach of MORE: “It only takes four weeks from taking the sample to sequencing it and molecular analyses are substantially more cost effective when compared to an unspecified chemo therapy. Furthermore, targeted therapeutics and immunotherapies are subject to fewer side effects. Based on the mutation patterns of metastases we can adjust the second-line therapy individually to the patient in order to gently and effectively eliminate tumor cells.

Dietz S et al. (2017) Patient-specific molecular alterations are associated with metastatic clear renal cell cancer progressing under tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Oncotarget May 23. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18200