13/06/2019

Print PageNot silent at all

Cancer diseases are caused by changes in the genetic material. As a rule, genes that drive cancer growth (oncogenes) or counteract the development of cancer (tumor suppressor genes) are affected. In countless studies over the past decades, cancer researchers have analyzed which mutation plays which role in which type of cancer. However, they have largely focused on mutations that result in an altered amino acid sequence of proteins.

"A large proportion of the genetic alterations do not affect the amino acid sequence at all," explains Sven Diederichs, whose department is affiliated to the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), the University of Freiburg and the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK). This is because the genetic code for most amino acids has several "words" that differ in their last, third DNA building block. If a mutation affects this building block, nothing changes in the amino acid sequence and hence in the resulting protein. In the past, this was referred to as "silent" mutations, but now it is more likely to be "synonymous" mutations.

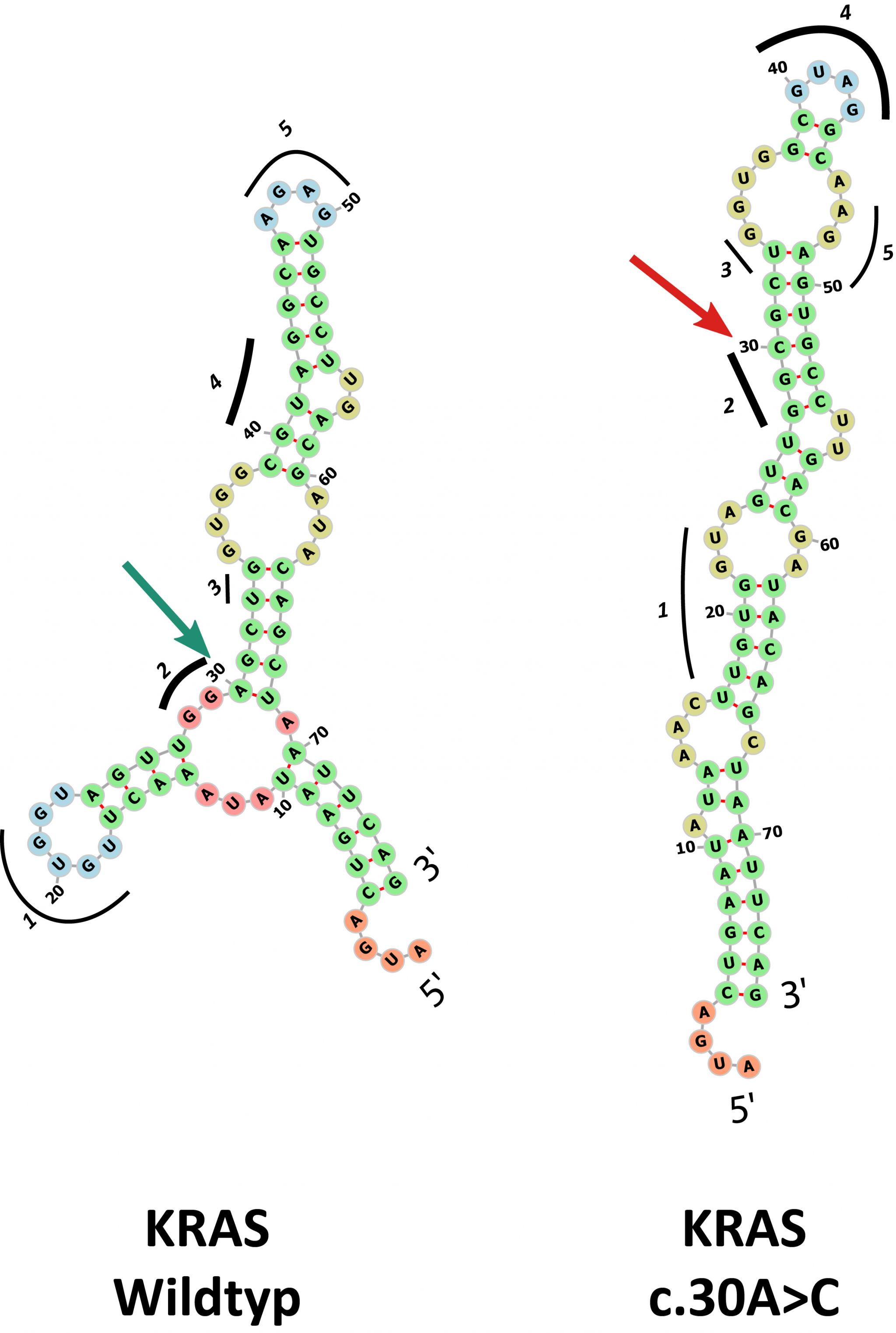

"Today we know that synonymous mutations play a role in many diseases and can, for example, affect the response of cancer to therapy. Nevertheless, their importance for the development of cancer is by no means as well understood as that of protein-changing mutations," said Diederichs. Synonymous mutations can intervene in many ways in important cellular processes: They affect the stability of RNA, its three-dimensional folded structure or how efficiently RNA is translated into proteins.

Diederichs and his colleagues from Heidelberg and Freiburg have now created an extensive database that contains all synonymous mutations discovered in the cancer genome and couples them with comprehensive additional information: What is the function of the affected gene, which position within the gene is mutated? In which cancers has the mutation been discovered so far and how often?

The SynMIC database contains a total of 659,194 entries concerning 88 different types of cancer. "Colleagues can use it as a reference book to obtain simple and comprehensive information about synonymous mutations that occur in the cancers they are dealing with," said Diederichs.

Using the important oncogene KRAS as an example, Diederichs and his team of researchers demonstrate in detail how synonymous mutations that have actually been discovered in cancer patients affect the RNA structure and protein production.

An estimated eight percent of all carcinogenic mutations affecting a single DNA building block are synonymous mutations. Previously, researchers had assumed that these supposedly "silent" mutations were not subject to selective pressure in cancer. But then they should be more or less randomly distributed over the genome - which is not the case, as the detailed decoding of cancer genomes in recent decades has shown.

Diederichs and colleagues now found another argument that strongly argues against the random hypothesis: Particularly at the beginning of all protein-coding gene segments, they mapped considerably fewer mutations - protein-changing as well as synonymous - than in the further course of the genes. "This is an indication that any mutation in this area has a stronger effect on the cell. Selective pressure could then prevent mutated cells from being able to assert themselves," said Diederichs. "And this selective pressure would then obviously also exist against synonymous mutations.

To the data base it goes under: http://synmicdb.dkfz.de/

Yogita Sharma, Milad Miladi, Sandeep Dukare, Karine Boulay, Maiwen Caudron-Herger, Matthias Groß, Rolf Backofen, Sven Diederichs: A pan-cancer analysis of synonymous mutations.

Nature Communications 2019, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-10489-2