05/12/2019

Print PageBetter understanding the development of aggressive embryonic brain tumors

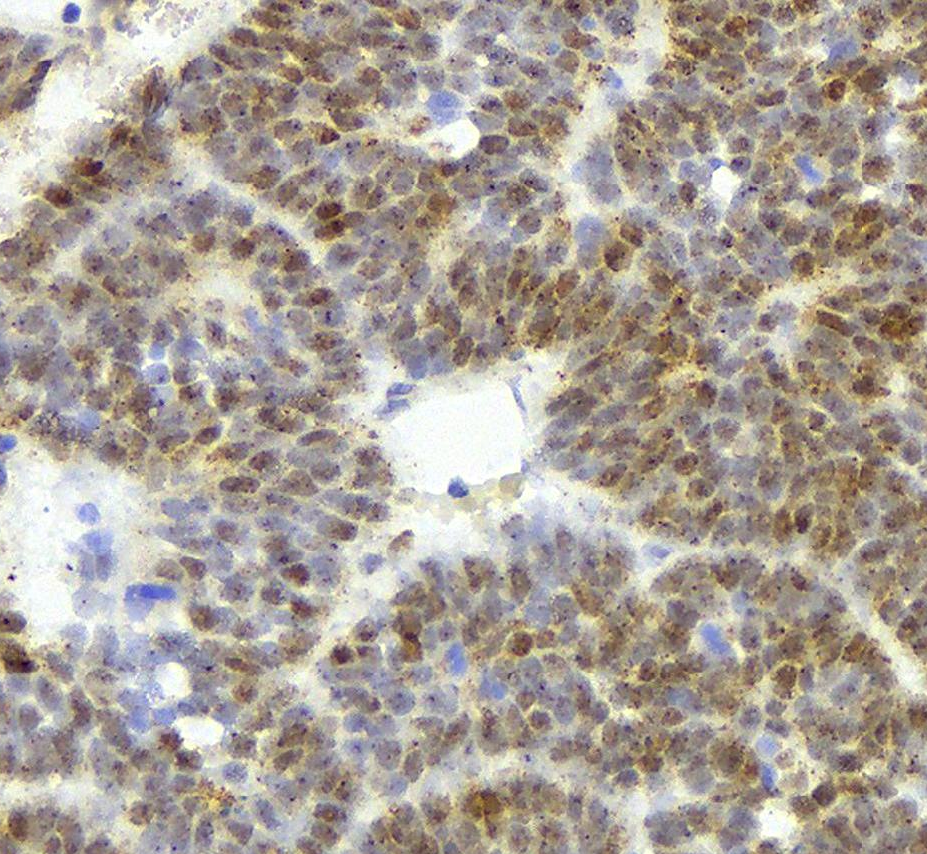

ETMR ("Embryonic Tumors with Multilayered Rosettes") are a group of particularly aggressive brain tumors that occur mainly in children under the age of four. They are considered to be most difficult to treat and usually lead to death within a very short time. In Germany only a few cases of ETMR are diagnosed every year, but worldwide there are probably about 100 to 200 new patients per year. The low number of cases complicates scientific work on this tumor group. So far, little is known about the origins and evolution of ETMR. Thusfar, there are no effective treatment methods.

To gain better insight into the biology of ETMR, a working group led by Marcel Kool, KiTZ scientist and group leader in the Department of Pediatric Neurooncology at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), examined the tumor tissues of 193 patients using state-of-the-art DNA analysis technologies and advanced molecular techniques. "We were able to characterize the tumors, both at primary diagnosis and at relapse, at the molecular level - to create a comprehensive overview of the molecular landscape of this type of cancer”, he explains. "Our analyses are the most extensive studies to date on potential drivers of tumor growth in ETMR," adds KiTZ Director Stefan Pfister, Head of the Department of Pediatric Neurooncology and expert in targeted therapies at the DKTK. "This represents a valuable source for new therapeutic approaches to this type of cancer."

In former research studies, about 90 percent of the tumors showed a genetically abnormal change on chromosome 19 of the tumor genome. The KiTZ scientists were now able to prove that the ten percent who do not possess this specific mutation called C19MC amplification is by no means a different tumor group. KiTZ researcher Sander Lambo, who carried out most of the research work, explains: "We were able to show that ETMRs are very similar at the molecular level, regardless of the presence of the marker C19MC and also independent of the tissue condition and the location of the tumor in the brain.”

The researchers noticed that in tumors without C19MC amplification, DICER1 mutations were particularly common. This mutation is also found in the germ cells of the children affected and is thus already present at the embryonic stage of development. It is known that children with this DICER1 germline mutation are at an increased risk of developing tumors in childhood. The studies indicate that ETMR also belongs to this group of DICER1 syndrome associated cancers.

Kool's research group discovered a number of other molecular abnormalities in the course of their molecular analyses, including the accumulation of so-called "R-loops." These unusual DNA-RNA structures may be the key to new treatments in ETMR: "Earlier studies suggested that R-loops could serve as targets for new therapeutic options," explains Kool. "We too were able to find first indication for this in our investigations."

Original publication:

Lambo et al.: “The Molecular Landscape of Embryonal Tumors with Multilayered Rosettes at Diagnosis and Relapse.” Online available here.

An image for this press release is available for download here.